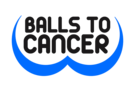

NHS England figures show that a total of 79,573 urgent cancer referrals were made by GPs in England in April 2020, down from 199,217 in April 2019

Cancer experts have warned thousands of patients who could have been saved may die unless the Government provides urgent help, after figures show the number of people sent for urgent cancer investigations has plummeted by 60 per cent due to the coronavirus pandemic.

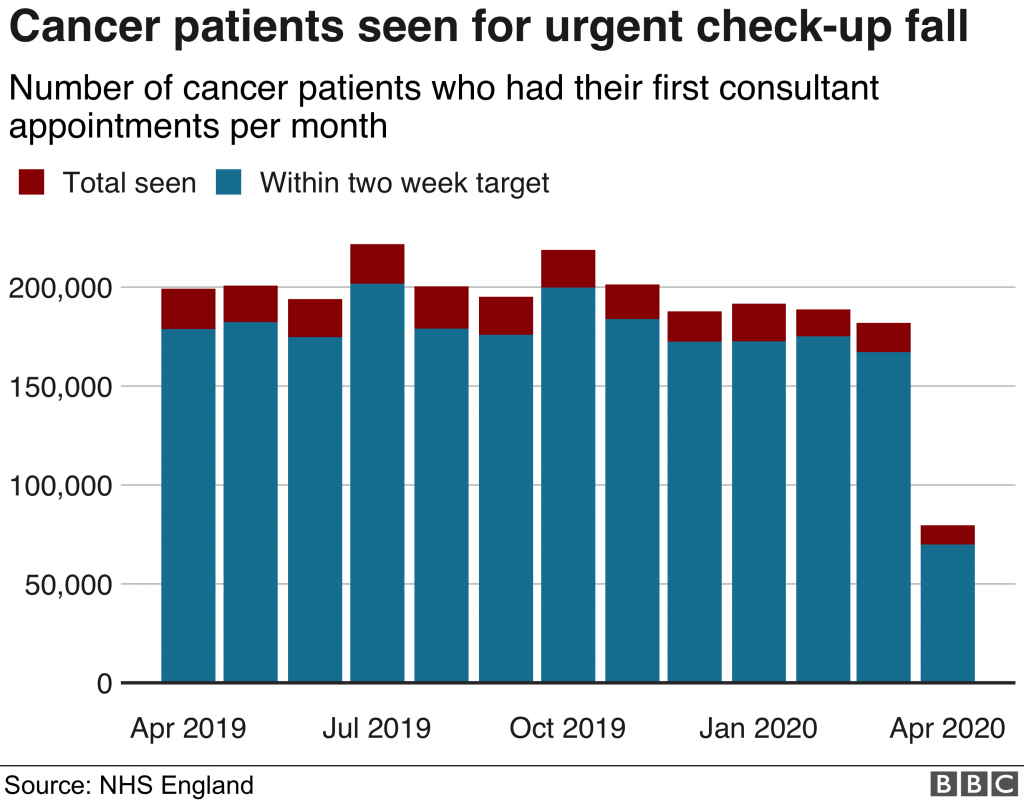

NHS England figures show that a total of 79,573 urgent cancer referrals were made by GPs in England in April 2020, down from 199,217 in April 2019. Urgent breast cancer referrals showed an even bigger drop: down from 16,753 in April 2019 to 3,759 in April 2020, a fall of 78 per cent. The number of people in England who had to wait no more than two months from GP referral to first treatment for cancer was also down 20 per cent – from 13,519 in April 2019 to 10,792 in April 2020.

Professor Karol Sikora, chief medical officer at Rutherford Health and former head of the World Health Organisation’s cancer program, said: “The bottleneck is in the diagnostic phase. We’ve known that but we didn’t know how big it was going to be and 60 per cent is a very significant drop.

“And it’s because partly people have been too frightened to come forward and speak to their GP, and partly the poor old GPs are faced with a collapsed service: he can’t get an endoscopy or a scan because everything was shut.

“The NHS moved into Covid-19 and did incredibly well. Now, we’ve got to pick up quickly. Cancer doesn’t wait, it doesn’t take Easter off. And there’s still a lot of people out there who’ve got cancer and don’t know it.

“We are going to lose far more people to cancer than we should. I’ve spent my life fighting this relentless disease, the consequences of the delayed treatment and diagnosis we’re seeing will be severe. It’s going to take another national effort – the fightback starts today.”

‘Covid-free’ hubs

The NHS has created “Covid-free” cancer hubs in hospitals to provide surgery while private hospitals have signed an unprecedented deal with the health service to treat patients, but it has not prevented a dramatic fall in referrals.

“The dramatic fall in the number of urgent referrals and the drop in people receiving treatment on time in April is hugely concerning. It means that tens of thousands of patients are in a backlog needing vital cancer care.

Professor Peter Johnson, NHS national clinical director for cancer, said: “These figures show that over the last three months NHS staff have been working incredibly hard to ensure that essential and urgent cancer treatment has been able to go ahead safely for thousands of people.

“But they also show what we have heard already, that many people have put off seeing their GP for possible symptoms due to fear of catching the virus or not wanting to burden staff. Lives are saved if more people are referred for checks, so my message to anyone who has a worrying symptom is: the NHS is here for you and can provide safe checks and treatment if you need it, so please help us help you, and get in touch with your local GP like you usually would.”

A&E attendances fall

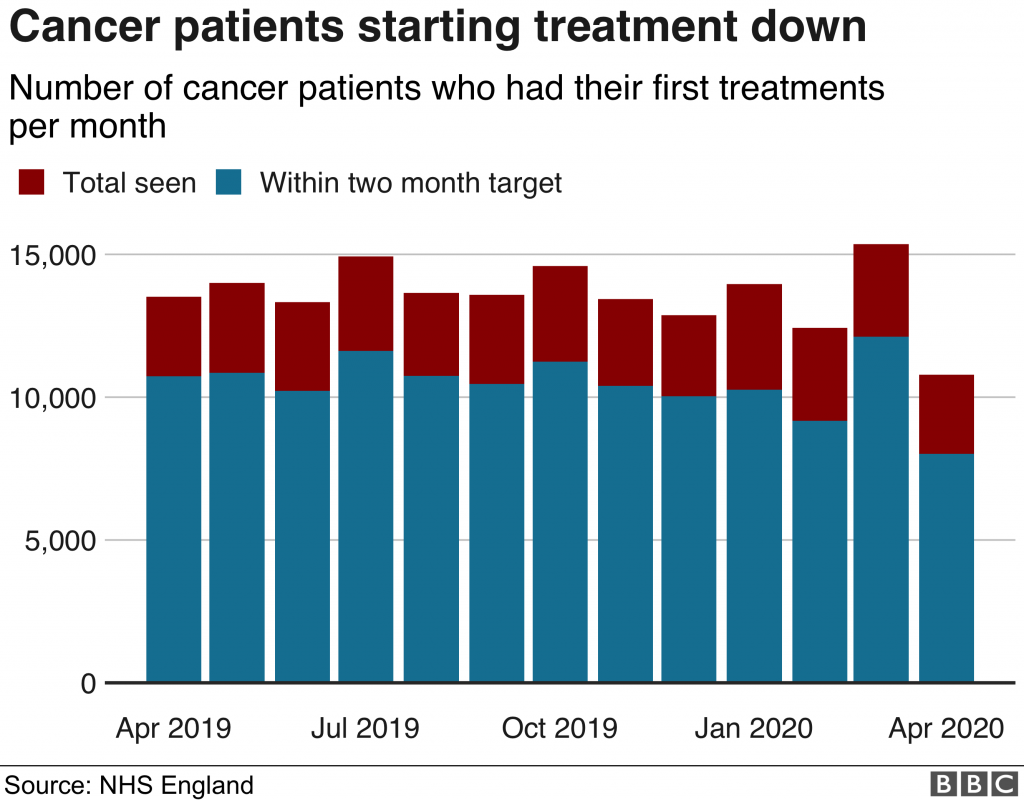

Separate figures from NHS England show the number of patients admitted for routine treatment in hospitals in England in April 2020 was 41,121 – a sharp fall of 85 per cent on the equivalent number for April 2019 (280,209).

Source: I News